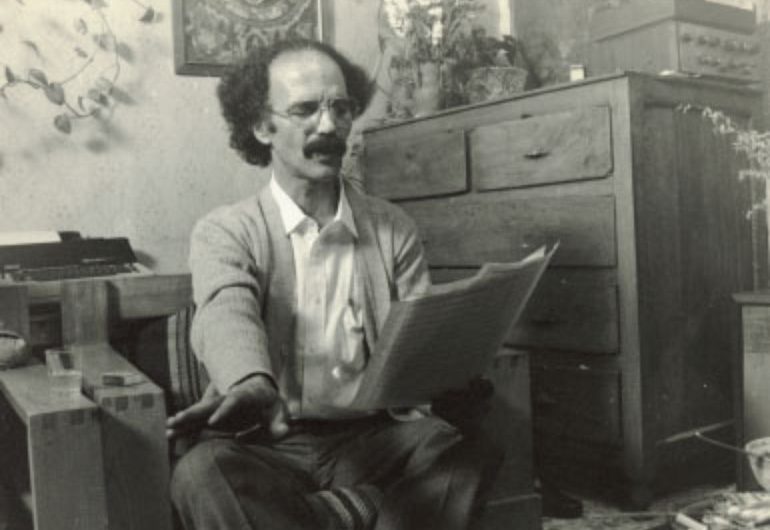

Houshang Golshiri

Writer, critic and editor of fiction, he was born in Esfahan in 1937 and grew up in Abadan, southern Iran. From 1955 to 1974, Golshiri lived in Isfahan, where he graduated in Persian language and literature from the University of Isfahan. He then taught in primary and secondary schools in the surrounding cities.

Golshiri began writing novels in the late 1950s. His publication of short stories in “Payam-e Novin” and elsewhere in the early 1960s, the founding of “Jong-e Isfahan” (1965 – 1973 ), the leading literary magazine of the time published outside of Tehran, and its involvement in efforts to reduce censorship of imaginative literature gave it a reputation in literary circles. Golshiri’s first collection of short stories was “Mesl-e hamisheh” (As always) (1968). Then came the book that made him famous, his first novel “Prince Ehtejab” (1968/1969). The latter is a story of aristocratic decadence, which implies the inadequacy of the monarchy in Iran. Shortly after the production of the popular film based on the novel, the Pahlavi authorities arrested Golshiri and imprisoned him for almost six months.

In 1978, Golshiri left for the United States. Upon returning to Iran in early 1979, Golshiri married Farzaneh Taheri, whom he credited with writing his last works. In 1990, under a pseudonym, Golshiri published a translated short story titled “The King of the Enlightened,” an indictment of the Iranian monarchy, which questions Persian literature, the Tudeh party, and the Islamic Republic. After a long period of illness, Golshiri died on June 6, 2000 at the Iran Mehr Hospital in Tehran.

“Prince Etehjab harbored the frustrating certainty that it was all useless. Sempiternal would be the connotation that came from that black and white photo of his grandfather – as if it were an epidermis subjected to taxidermal fatum. That perennial image survived in all that panoply of books, photos and contradictory anecdotes. But he longed to know – not just for himself but also for Fakhronessa; he wanted to penetrate that epidermal substrate, dispel the darkness of photographic chiaroscuro and read the cryptic and recondite message hidden between the lines of those volumes. So he said out loud:

– “I have to do something about it.”

He coughed. The weight of his gaze fell on that ballet of eunuchs and valets and he bellowed: “I don’t want to see you.” “Go away”. Among the women of the harem and the slaves who fought each other (naked?) The roar of that ancient laughter could certainly be felt. Satisfied and exultant, he threw down some pieces and the agonizing female contest began, like a vivid, whitish mass. Every now and then a limb could be glimpsed and he smiled. As a gap opened in that crowd, the great ancestor threw new pieces. Beyond that scene, the grandfather remained upright and undaunted. Or would he be sitting? A vague sketch of a small and large infant, or a large and thin infant with thinning hair. And the eyes? Dressed in hat, boots, sword and polished buttons. And his preceptors, ministers and advisers.

And he coughed loudly, aware that it would be quite a chimera to try to apprehend the longed-for image of his grandfather, seated on a couch or mounted on a docile steed, or laughing life-giving in the midst of that bloody mass. “

(Shazdeh Ehtejab Fragment)

Comments