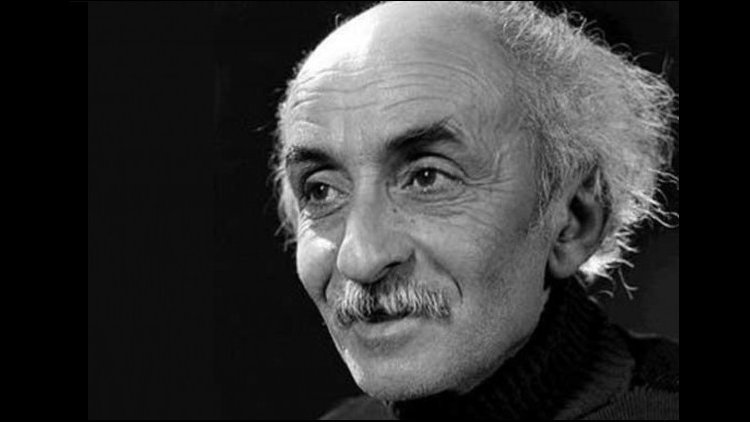

Nima Yushij

Nima Yushij (1897-1960), the first great poet of nimaic poetry, developed a poetic form that was later called new poetry or free verse to remove the restrictions of traditional rhyme and meter. Although he was not the only, or even the first, to attempt to modernize Persian poetry, he has been credited with the title of “father of modern Persian poetry.”

He was born on November 11, 1897 in Yush, a town in Nur, a city in northern Iran. His father, Ebrahim, was a strong supporter of constitutionalism. He could read and write, which made him a member of the Iranian elite of the early 20th century. Nima’s mother, Tuba, was the granddaughter of Hakim Nuri, a poet from the Qajar period.

It was in the midst of the Constitutional Revolution (1906-1911) when twelve-year-old Nima moved to Tehran (1909) to attend the Liceo San Luis, a French missionary school. One of his teachers, Nezam, recognized his poetic gift and encouraged him to write and compose poems.

Nima Yushich, who spent most of his life learning the methods of the masters, came to the conclusion that Persian poetry had to be changed not only in content, but also in form.

In classical Persian literature, prose and poetry were easily distinguished. Poetry, unlike prose, was symmetrical in its form and music. Even in works that juxtapose lines of poetry and prose, readers and listeners can easily distinguish between the two. Nima developed a different idea of the form and music of poetry. Nima’s formal innovations focus on rhyme, an important element in the form and music of Persian poetry. From the beginning of Persian poetry, rhyme has been one of its main characteristics. The division of the beyt (verse), a single poetic unit, into two hemistiches of equal metric value made the mechanical nature of the rhyme scheme in Persian poetry highly visible.

Nima revitalized rhymes in Persian poetry. Classical Persian poetry was based on the beyt (verse), and rhyme was an integral part of each beyt. However, in Nima’s style, there is no conventional beyond as the fundamental unit of poetry. For him, rhyme was a musical element to link related ideas, rather than the conventional beyt, in a poem.

In Nima’s new poetry, rhythm is fundamental. The poets in the new poem compose their poetry according to the rhythm of natural speech and not according to a predetermined set of meters. Visually, this choice ruins the aesthetics of the poem, as the hemistiches lose their traditional symmetrical balance; one line can contain a single word, while other lines can contain a long string of words. Harmony is also achieved in different ways. The monotony of the traditional metric stanza is replaced by a dynamic harmony that is achieved by accumulating the effect of the natural rhythm of spoken language. Finally, the new poetry seeks to move away from traditional poetry not only in abandoning the thematic system and rhyme, but also in the choice of content.

Comments